Otitis media means inflammation of the middle ear usually caused by infections. Otitis media can affect one or both ears and may lead to pain, hearing loss, speech and language delay.

How Does the Ear Work?

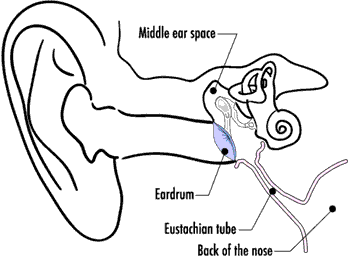

The outer ear collects sounds. The middle ear consists of the ear drum and three small ear bones. It is normally filled with air. When sounds strike the eardrum, it vibrates and sets the bones in motion. The vibration is passed to the inner ear.

A healthy middle ear is filled with air. Air enters the middle ear through the narrow eustachian tube that connects the back of the nose to the ear. When the system works normally, the pressure in the middle ear is the same as atmospheric pressure and this allows the ear drum and bones to vibrate normally.

What Causes Otitis Media?

Blockage of the eustachian tube and the inflammation in the middle ear from bacteria or viruses lead to the accumulation of fluid behind the eardrum. The eustachian tube is small, and in some children, does not function well. Its function can also be affected by upper respiratory infections and allergies. When the tube is blocked fluid builds up in the middle ear causing pain, pressure, hearing loss. If the pressure increases too much the eardrum ruptures and pus drains out of the ear. More commonly, the pus and mucus remain in the middle ear. This is called middle ear effusion or serous otitis media. Often after an infection has passed, the effusion remains lasting for weeks, months, or even years.

What Will Happen at the Doctor’s Office?

When children have recurrent infections or persistent fluid children will be referred to an ENT doctor. The doctor will check for changes indicating otitis media such as redness, retraction, poor mobility or fluid behind the eardrum. Two other tests may be performed for more information. An audiogram tests if hearing loss has occurred by presenting tones at various pitches. A tympanogram measures the air pressure in the middle ear to see how well the eustachian tube is working and how well the eardrum can move.

When is surgery necessary for Otitis Media?

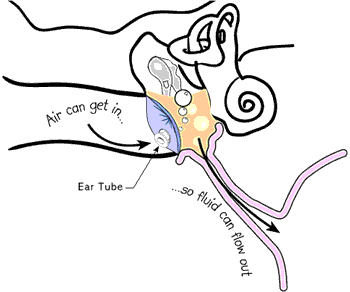

When otitis media happens repeatedly or if fluid is present for a prolonged period an operation, called a myringotomy, may be recommended. This involves a small surgical incision (opening) into the eardrum to promote drainage of fluid and to relieve pain. The incision alone heals so fast that it often closes before the infection and the fluid are gone. An ear tube (pressure or ventilation tube) is usually placed through the incision. It prevents fluid from accumulating and thus improving hearing.

Otitis media may recur as a result of chronically infected or enlarged adenoids. If this becomes a problem, your doctor may recommend removal of the adenoids called an adenoidectomy. This can be done at the same time as ventilation tubes are inserted.

How do ear tubes work?

During an ear infection, fluid builds up behind the eardrum. Ear tubes are small, plastic or metal, hollow tubes inserted into the eardrum (also called the tympanic membrane). Ear tubes allow fluid to drain out of the middle ear and for air to get in. Over time this “ventilation” helps to decrease swelling in the Eustachian tube and allows the middle ear to function more normally. This is why ear tubes are sometimes called ventilation tubes or pressure equalization tubes (PE tubes for short).

How are ear tubes put in?

An ENT surgeon makes a small incision in the eardrum using a microscope. The tube is then placed through this hole. Because children cannot hold still for this procedure, it is performed in the operating room under general anesthesia.

The procedure itself usually takes no more than 10 or 15 minutes. After surgery, the child is monitored for a short period then allowed to go home.

What can I expect after surgery?

Usually the recovery is mild and quick. Your child may have a low-grade fever (99° to 100°F) for a day or two after surgery. There may discharge from either ear (pink, clear, yellow, or even bloody in color) for 2 or 3 days. Your doctor may give you some ear drops to use after surgery to help control the drainage. You can expect your child to be back to his or her regular diet and activities within 24 hours after surgery.

Your child’s ears do not require any special care after surgery. You do not have to worry about getting water in the ear canals with bathing, washing the hair, or even swimming in shallow water. If your child is older and dives deep under water while swimming, or if they get infections after exposure to water your doctor may suggest limiting water exposure and use of ear plugs while swimming. Airplane travel is okay with ear tubes which prevent the painful pressure changes that children can otherwise experience during air travel. If an infection develops after the surgery you will notice drainage or a bad smell from the ears. You should call primary or ENT doctor if your child’s ears are draining. Don’t panic this is better than the fluid being trapped and usually responds quickly. Some children may a second set of tubes if they continue to have otitis media.

Risks of Myringotomy and pressure equalization tube surgery

This type of surgery is extremely common and safe procedure with infrequent complications which may include:

- Perforation: After the tube comes out or is removed the hole may not heal resulting in a small hole in the ear drum. The hole can be patched through a surgical procedure called a tympanoplasty or myringoplasty.

- Scarring: Any irritation of the ear drum (recurrent ear infections), including repeated insertion of ear tubes, can cause scarring called tympanosclerosis or myringosclerosis. In most cases, this causes no problem with hearing and does not need any treatment.

- Tube related problems: This can include early or late extrusion. If a tube comes out early fluid may return and repeat surgery may be needed. Ear tubes that remain too long may result in perforation or may require removal by an otolaryngologist.

- Infection: Ear infections can still occur with a tube in place. However, these infections are usually infrequent and resolve more quickly. They often resolve on their own or with antibiotic drops. Oral antibiotics are rarely needed. In rare cases the drainage might be chronic.

Resources: